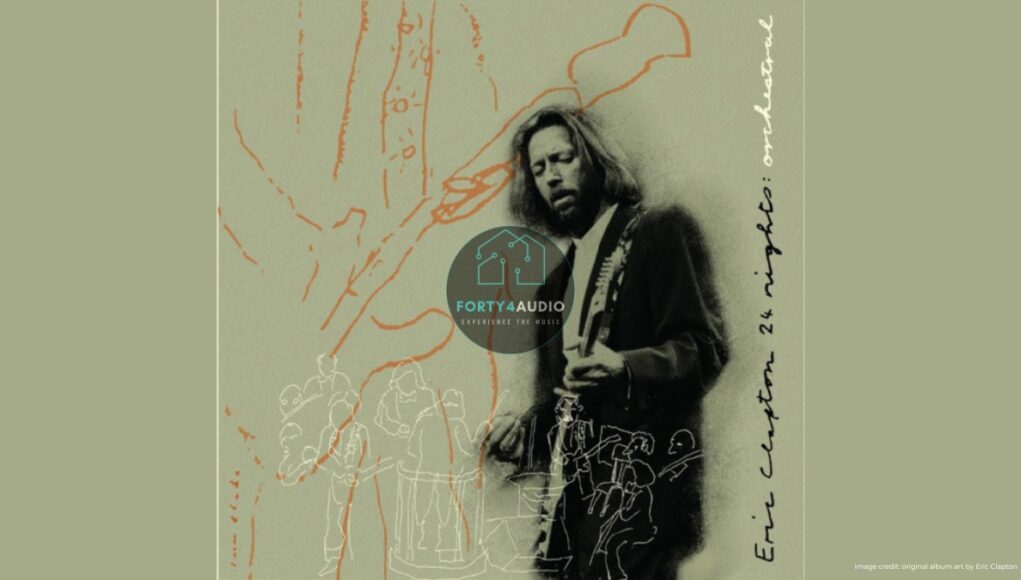

There is a particular quiet that lives inside 24 Nights: Orchestral.

Not the quiet of absence, but the quiet that arrives when familiar music is placed inside a larger room and asked to slow down.

These performances come from a long Eric Clapton residency at the Royal Albert Hall, a space already heavy with memory. Within that run, the orchestral nights feel less like spectacle and more like a private experiment conducted in public. Clapton stands at the center, but the sound belongs equally to the air around him, shaped by Michael Kamen‘s arrangements and the patient breath of the National Philharmonic Orchestra.

The album opens with “Crossroads.” As an invitation. The orchestra does not rush the entrance. It widens the song’s horizon, allowing the guitar to speak without urgency. The familiar structure remains, yet the space between phrases feels newly exposed.

“Bell Bottom Blues” follows, softening the emotional temperature rather than escalating it. The strings do not dramatize the sadness; they cradle it. This is music that understands restraint, that knows when to sit beside a feeling instead of underlining it.

With “Lay Down Sally,” the sequencing shifts gently. Rhythm becomes more conversational. The orchestra sways rather than swells, and the song’s easy familiarity is reframed as something reflective, almost inward.

“Holy Mother” arrives like a pause that deepens the room. The orchestration leans toward solemnity without heaviness. It asks for attention, not reverence. Repeated listens reveal how carefully the arrangement avoids resolution too early.

“I Shot the Sheriff” resets the body. The groove remains, but it is filtered through discipline. The orchestra holds the rhythm in place, keeping the song grounded, reminding us that power does not require excess volume.

“Hard Times” feels transitional, both musically and emotionally. Its placement matters. It acts as a hinge between familiarity and exploration, preparing the ear for what follows.

“White Room” opens outward again as if Cream is still at the forefront. The orchestral textures create a sense of distance, as if the song is being viewed from across the hall rather than from the stage. It feels less like performance and more like recollection.

That sense of distance deepens with “Can’t Find My Way Home,” featuring Nathan East on lead vocals. The change in voice alters the album’s center of gravity. The orchestra listens closely here, leaving space for the song’s fragile honesty. This track often reveals itself slowly, especially on repeat listens late at night.

“Edge of Darkness” shifts the album into cinematic territory. The orchestration becomes narrative rather than supportive. This is where Kamen’s creative voice is most clearly felt, guiding the album toward its extended closing arc.

“Old Love” brings the guitar back into emotional focus. The orchestra does not compete; it waits. The song unfolds patiently, and its length becomes part of its meaning. Time is allowed to stretch.

With “Wonderful Tonight,” the album turns intimate again. The arrangement is careful, almost domestic. It feels like a moment held at arm’s length, familiar yet newly vulnerable in this setting.

“Layla” arrives late, as it should. Stripped of urgency and reframed by orchestration, it no longer demands attention. It simply exists, letting the listener decide how close to stand.

Then the album shifts from songs into composition.

“Concerto for Electric Guitar – Part 1” marks a fundamental change in listening posture. The guitar is no longer the focal point above the orchestra; it becomes a voice within it. Themes are introduced slowly, passed between sections, returned to the guitar with subtle variation. The writing is deliberate and spacious, allowing tension to accumulate without rushing toward release.

In “Concerto for Electric Guitar – Part 2,” that tension is given room to resolve. The dialogue between orchestra and guitar deepens, with long arcs replacing song forms. The guitar solo is expressive without being showy, shaped by the orchestra rather than set against it. What emerges is not a fusion of styles, but a shared language built over time.

Together, the two parts do not function as a finale in the traditional sense. They feel more like arrival. The album stops performing and begins to exist, sustained by listening rather than momentum.

By the time the final notes fade, the sense of performance has quietly disappeared. What remains feels closer to presence than memory.

A room.

Instruments playing as one.

And time allowed to move at its own pace.